Counting Polycubes of Size 21

There are 1,636,229,771,639,924 unique 3D polycubes that can be constructed with 21 cubes.

There are 1,636,229,771,639,924 unique 3D polycubes that can be constructed with 21 cubes.

I calculated this number over a period of 10 days in the Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud using Stanley Dodds's amazing algorithm (see below), which I ported to rust. In this post I'll give some background on my efforts to compute this value.

The canonical source of many integer sequences, including many polycube and polyomino sequences, lives at the OEIS. The relevant sequence here (polycubes containing cubes) is sequence A000162, where you'll find the rest of the known values in this sequence as well as a link to Dodds's code.

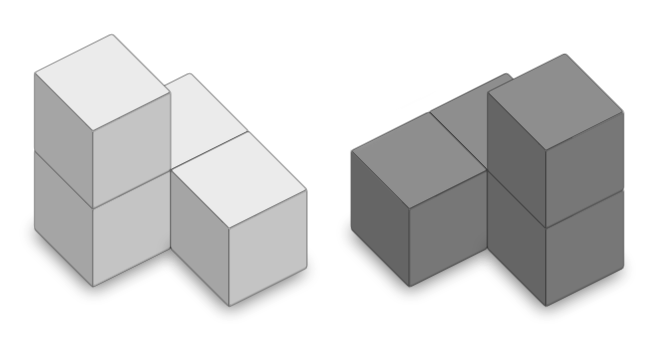

Above, we have some example polycubes from Wagyx's viewer app (see discussion of this app here).

A mid-2023 Computerphile video on YouTube was about writing code to count polycubes. The idea is to count the unique 3D shapes that can be formed by joining together some number, , cubes on their faces. A "unique shape" is one that cannot be rotated to match another shape. Some pairs of shapes mirror each other, where one cannot be rotated in any direction(s) to match the other. These pairs count as two unique shapes. One example is this pair of shapes shown on Wikipedia's Polycube article:

(This above image is based on an image appearing on that Wikipedia page, and is thus released under the CC BY-SA 4.0 license.)

There is no straightforward way to simply calculate the number of polycubes of size — as far as we currently know, they have to be more or less individually counted. This problem is deceptively difficult. According to the OEIS, as of 2007 we (as a species) had only been able to enumerate the polycubes up to ! While 16 doesn't seem like a lot of cubes, apparently 59,795,121,480 unique 16-cube shapes exist.

Algorithms

The Computerphile video does a nice job of laying out the problem. There are 24 possible rotations for each shape in 3 dimensions, so a straightforward algorithm computes all possible shapes, and keeps a hash table or similar to prevent counting duplicates. Then for each shape, apply all 24 rotations and take the hash of each rotated shape. If any one of those hashes appears in the hash table, disregard that shape as a duplicate. Otherwise, add one of those hashes to the hash table. As grows to 16, 17, 18, etc., that table would quickly exhaust any computer's memory.

The best solutions would therefore not involve a table at all. I tried to think of a way to hash polycubes independent of rotation, and quickly ran into the limits of my own abilities.

presseyt on GitHub produced a nice algorithm for table-less counting, along with some nicely-performing JavaScript code. I was able to port the JavaScript to python, and running with pypy, it was much faster. presseyt's algorithm is perfectly parallelizable: it can be split into individual smaller subtasks (even millions or billions of them) that can be completed in complete isolation. This sort of algorithm could theoretically be run over a huge distributed network.

I then spent a few weeks porting my python to rust, and optimizing that code. I ended up with a decent result (here's my GitHub repo), but computing for would take 30 days or more on my M1 Mac mini. My realistic goal at this point was to calculate for and or so, which at the time were not listed on https://oeis.org/A000162.

Note: I was unaware that by this time some folks, including pbj4 on GitHub, had already computed up to and had been posting those results to the GitHub repo associated with the Computerphile video.

A New Algorithm

Then I noticed that the OEIS entry had been updated! After 16 years the sequence had been extended while I was working on this problem! Counts for and were added, and also and even !

I don't know how coincidental it was for the Computerphile video to come out in mid-2023, then, later that year, the OEIS entry was extended for the first time since 2007. I would imagine it's not very coincidental.

The OEIS entry was updated by Stanley Dodds. Their update included C# source code, presumably the code used to calculate the, unthinkable just days prior, count for . Luckily, I already had mono installed on my M1 mac, and was able to compile and run the C#. As a test run, it output for in less than one second, where my previous best, with a rust program, took 45 seconds. Wow! 45 seconds down to just nothing for !? Then I tried . After about 25 minutes (with 8 threads on my M1 Mac mini), it returned the proper count: beyond 457 billion. This was truly mind-blowing performance. My previous best solution would have taken more than 30 days! And this was C# code!

While I fully understand presseyt's algorithm, I haven't yet taken the time to do the same for the overall methodology of Dodds's. The first portion of Dodds's incredible algorithm counts "nontrivial symmetries," then, separately, counts "trivial symmetries." As far as I can tell, the second portion is some sort of traversal using stacks and a table to somehow count all rotations of all polycubes of cubes, without repeating any. For the final step, it simply sums the counts from the first and second portions, then divides that sum by 24 to end up at the count of unique shapes.

A New Goal

My goal was instantly changed: calculating for and now seemed possible. To calculate those, I figured it would make sense to port Stanley Dodds's code to rust and then to run it on a beefy machine in the cloud.

To save some time with the port, and also to try out the latest LLM toy tool, I tried out Microsoft's new Copilot app on the Mac. By carefully copy/pasting in small portions of the C# code, and asking to port each one to rust, I quickly had a rough outline of the rust port. Using Copilot was complicated by the limit on the input size, but it produced mostly usable rust code. Overall though it probably didn't save me a ton of time. I then spent several days correcting obvious errors in gpt4's code, and finding and fixing a few harder-to-find problems. I was finally able to get correct output with the rust version of Dodds's algorithm, and it seemed to be several times faster than the C# version.

This is where I made a few small mistakes that set me back a few days. At this point, I was excited to start calculating for , and I hurried to get my rust code ready to run on an AWS EC2 instance. I added multi-threaded calculation of "nontrivial symmetries," the faster first portion of the calculation, and the ability to hard code those results so they don't have to be re-calculated every time the program is run. I added some code to output running time and give an estimated time remaining.

After confirming how many worker thread tasks the counting could be split among (it was 63 tasks for ) I needed to see if it could be completed in a realistic amount of time running on an AWC EC2 instance. I then ran my rust code on my home M1 Mac mini to see how long each thread task would take. I was really excited to see that my home machine finished one worker task in less than 24 hours! With that running time confirmed, I thought I could fire up an AWS instance with many CPUs and get a result relatively quickly.

I looked at 64-vCPU AWS EC2 pricing. I saw the c7g and c6g instances were the cheapest, but they were grayed out in the instance type selection menu. Since I figured the running time wouldn't be very long, and it doesn't require a lot of memory, I shrugged off the c7g / c6g instance types and launched the cheapest compute-optimized 64-vCPU instance type I could find: a c7a.16xlarge instance.

While running my initial rust code in EC2 for a couple days, I made a few realizations. I stopped that instance, sacrificing my partially-computed results in the process.

Initial AWS EC2 Mistakes

The first mistake I made there was not printing the actual count found for each worker thread task. Since each worker thread task finds its own completely independent count (enumeration of a subset of the shapes of polycubes of cubes), if I had simply printed those tasks' counts to the screen, I could have re-used them to resume computation.

This leads me to my next mistake: not realizing that worker tasks do not all take the same time to run! In fact, the slowest worker tasks take about five times as long to run as the fastest ones:

This means the overall running time is about 5 times as long as I thought it would be (since I was using a separate vCPU and thread for each task). This also means that if starting 63 threads at once, one for each worker task, the fast ones will finish and then sit idle (for days!) while the long-running jobs keep running. I saw hints of this while testing the code, but I didn't stop to investigate this enough.

The next mistake I made here was a real forehead-slapper. I was developing my rust code using cargo and testing with cargo run --release to compile and run with performance optimizations. On the EC2 instance, I didn't want to bother setting up a cargo project. I kept my code constrained to a single source file, without using any external crates, so I just compiled with rustc polycubes.rs — which doesn't compile with optimizations! This means the code I was running was running at half speed, and actually probably slower than that, compared to the speed I was seeing with cargo run --release on my machine. If I had just instead used rustc -C opt-level=3 polycubes.rs the code would have run at the expected speed, more than twice as fast.

The last mistake I'll list here has to do with AWS EC2 instance types. The g AWS EC2 instances are ARM-based, and presumably cost Amazon a lot less power to run. They're the cheapest compute-optimized instance type, which I did initially see, but I didn't think my running times would be long enough to matter so I just ignored the fact they those "g" instances didn't appear to be available. I didn't realize the EC2 web console UI limited the instance types by the architecture of the selected AMI. To run the cheaper and faster "g" instances, I needed to browse the full list of AMIs, then filter for ARM AMIs — for example when using the Amazon Linux at the top of the ARM AMIs list, that itself needed another option to be toggled to use ARM. In my defense, I clicked the big "Amazon Linux" button, which does have an ARM variant...

AWS Improvements

The few longest-running worker tasks are at the end of the list of tasks to run. Most of the tasks, including just about the first half of all tasks, are the fastest. I realized that by running the tasks in reverse order, we can start the few long-running tasks first. While those long-running tasks continue to run (again, some of which take about five times as long to run as a the short tasks), an individual vCPU has plenty of time to run several faster tasks. This means that by running the tasks in reverse order, and with a smaller number of vCPUs, we'll have the same overall run time, less idle vCPU time, and less overall AWS cost. Because of that 5x runtime factor, I figured it would be safe to run with 1/4 of the vCPUs I was previously running — 16 vs the original 64. This means the AWS EC2 pricing would be 1/4 the cost of my initial attempt. (See the Running times and costs for tasks and vCPUs section for more information on this.)

I also added printing of timestamps and counts when each individual task is completed. After hard coding any previously-calculated task results, by first doing a lookup before kicking off a task, we can skip any task whose count has already been calculated. This will save me in case my instances are killed.

Next, I experimented with the performance of the "g" instance types. Both c6g and c7g are much cheaper than the c7a instance I was initially using — and I found c7g to be ~10% more expensive but well more than 10% faster than c6g.

Lastly, I compiled my single rust source file with rustc -C opt-level=3 polycubes.rs. This alone sped things up by more than 2x.

Running Time+Cost vs. Threads

For EC2 instances in the AWS cloud, hourly on-demand pricing generally scales linearly with the number of vCPUs. For example, a 64-vCPU instance generally costs twice as much per hour as a 32-vCPU instance. With this in mind, we can use the number of thread tasks that need to be run, and their individual running times, to find an instance size that balances overall running time and cost.

Of course, we don't know the exact running time before we actually run the code. But by looking at the running times for thread tasks for smaller values of , I felt like I could see how the running times increased relative to an increase in . After I launched my second attempt at in AWS, on a 16-vCPU instance, I generated the below data to double-check my selected instance size.

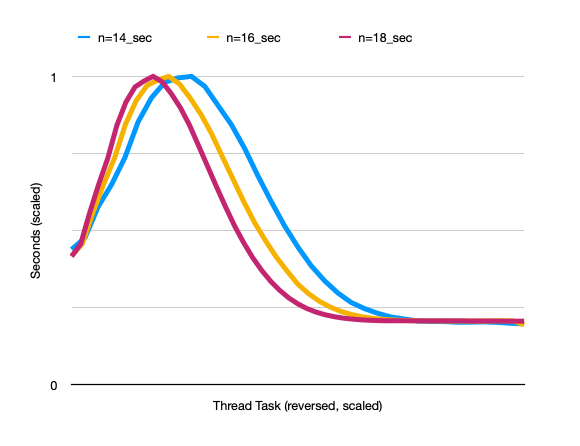

Here, I've charted the running times of each thread for , , and . Both the thread running times and the thread numbers have been scaled as a proportion of the maximum, so everything is aligned:

Every increment of adds another 8 thread tasks, which for this chart means the line shows the individual running times of 51 tasks. Interestingly, the 10th task always seems to be the longest running, and the peak of each of these lines is at the 10th task.

We can see that as is increased, the duration of the longest-running threads is not increased relative to the fast threads. Also, we can see the "hump" gets more narrow as increases — this shows that the proportion of long-running threads actually decreases as is increased. As increases, having the same long/short task duration ratio and with proportionally fewer long-running threads, we don't need to dedicate more vCPUs for long-running threads. Instead, we could use more vCPUs to reduce the overall running time without incurring too much wasted cost of idle vCPU time. On the other hand, since AWS generally only offers 8-, 16-, 32- and 64-vCPU instances that are relevant here (and nothing in between those vCPU quantities) it doesn't seem like it makes that much of a difference.

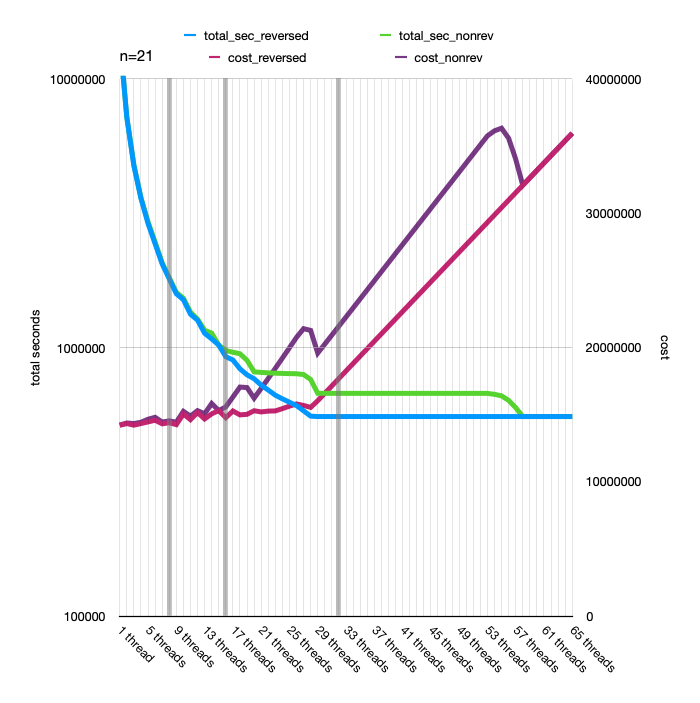

Charting for

As we change the number of threads a hypothetical cloud machine can run, we affect both the running time and the total cost of running the calculation. For the below chart, I've plotted both running time and cost for 1-60 threads for . I've added a dark gray line for available AWS EC2 instance sizes at 8, 16, and 32 threads. The blue and green running time lines are plotted on a log scale, and the exact units are omitted here since this is a hypothetical machine. The magenta and purple are plotted on a linear scale, and again I'm omitting the units of the hypothetical cost (calculated with ). When "reversed," we start with the long-running thread tasks, and "nonrev" we start with the fast thread tasks (see the chart above of individual thread run times).

You can see the "reversed" options are always at least as fast and cheap as "nonrev," and often faster and cheaper, so we'll just ignore the "nonrev" options.

You can also see that the overall running time drops as we add more threads until we reach the fastest possible running time. For , that happens with 25 threads.

But since Amazon only offers 8, 16, and 32-vCPU c7g instances that are relevant here, we'll consider just those. We see that while running the calculation on an 8-vCPU instance is slightly cheaper than the 16-vCPU, it's much slower. The 32-vCPU is a little faster than the 16 (remember than the blue line is plotted on a log scale), but it's considerably more expensive.

Again, I made these charts after having selected the 16-vCPU instances for my and calculations, and I'm relieved it showed I made a sensible choice. While Amazon does offer some 24-vCPU instances, they are much more expensive on a per-vCPU basis than the hypothetical 24-thread c7g instance plotted here.

Charting for

Now let's look at the same chart, but for :

As we go from to , we increase the number of thread tasks, but again the ratio of long/short tasks decreases (proportionally, more fast tasks than slow ones). This effectively pushes the lines in the chart further to the right, toward "more threads" being optimal.

If we try to find the best balance of speed and cost on both charts, we see that's at about 24 threads for and 28 or 29 threads for . Again, in both cases, those 24- and 28-vCPU instances don't actually exist and the real choice is between a 16- or 32-vCPU instance. Perhaps for or a 32-vCPU would actually be closer to optimal.

In retrospect, my choice of a 16-vCPU EC2 instance for looks to be cheaper but slower than a 32-vCPU instance.

AWS Running Times

The data in the chart above shows that with a 16-vCPU instance, the running time is theoretically 924,034 seconds, or about 10.69 days. The actual running time was 924,038 seconds.

For a 32-vCPU instance (which costs twice as much per hour) the running time would be around 553,253 seconds, or 6.40 days. Though much faster, the 32-vCPU instance would end up costing 19% more than the 16-vCPU instance.

Conclusions

This was a terrific winter programming project. I enjoyed working on this challenging problem, and optimizing my code (even if it was subsequently blown out of the water by other solutions!) similar to my winter of 2022 slog through the Advent of Code.

I got to dust off my skills with rust and AWS. On the rust side, working with threads was quite easy (compared to my similar efforts in python), and I learned a little about pointer arithmetic. The speed of rust is impressive, and it's great knowing the language and compiler are so strict you get the best of both worlds: speed and safety.

As for AWS... it's a little too much fun to browse AWS EC2 instance types and to launch them at a whim. There's a lot of computing power out there just waiting to be tapped into.

Lastly, I enjoyed watching the individual thread tasks complete, one by one as the days crept by, for the final count to be revealed.

Credits

All credit for enumerating polycubes of goes to Stanley Dodds and their breakthrough algorithm.

Dr. Mike Pound and the Computerphile channel on YouTube, and all the contributors at the associated GitHub repo, were of course the main inspiration for my work on this project.

My rust port of Standley Dodds's algorithm is available on GitHub.